Features

Traits and Genetics

Hot potatoes: potato varieties suited for climate change

The heat is on to identify potato varieties that can thrive through climate change.

March 25, 2020 By Rosalie Tennison

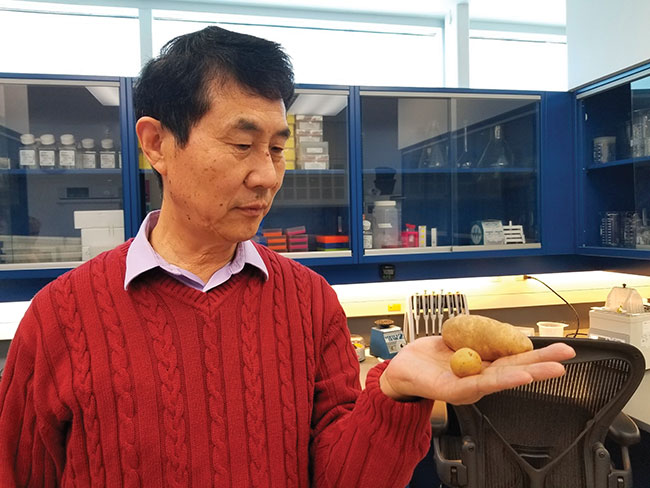

Xiu-Qing Li with AAFC in Fredericton is studying Canada’s current potato varieties to see which are the most heat-tolerant. Photo courtesy of Xiu-Qing Li.

Xiu-Qing Li with AAFC in Fredericton is studying Canada’s current potato varieties to see which are the most heat-tolerant. Photo courtesy of Xiu-Qing Li. With climate change heating up Canada’s crop land, identifying or developing new potato varieties that can grow in warmer temperatures is on the radar of Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) researchers. Potatoes originated from and still grow wild in the cooler climate of the Andes of South America, and research scientists have often mined these varieties for traits desired in North American cultivars. Canada’s potato-growing areas mimic the cool 20 C daytime temperatures that make the wild varieties so hardy. But what happens when the heat gets turned up?

Xiu-Qing Li of AAFC in Fredericton noticed that warmer summers are creating heat stress in Canadian potato crops. He began studying Canada’s current varieties to see which are the most heat-tolerant. He also hopes to identify the genes responsible for heat tolerance and to incorporate them into future varieties, either through genetic crosses or directional mutation.

“Climate change threatens the future production of potatoes, but some varieties are more heat-tolerant than others,” Li explains. “We want to continue to grow potatoes, but we need to use varieties that can tolerate heat stress.”

In a paper published in Botany [journal], Li quotes Statistics Canada data that revealed a 2016 yield decrease in Ontario potatoes of 17.2 per cent compared to the 2015 season. A trend of continuous decreases could severely hamper potato production in Canada and could also pose issues of food security with the rising world population. If the entire production of potatoes worldwide experiences similar yield decline, the future of this nutritious food source could be under threat. Li’s research focuses on getting in front of what could be a potential crisis.

Growers know that developing new cultivars can take a decade or more and, with predicted increases in temperature to be as much as two degrees by the end of the century, if not sooner, plant breeders need to start working towards varieties that can take the heat immediately.

Li and his team put 55 commercial cultivars under heat stress in a laboratory and studied leaf chlorophyll content, plant growth and tuber yield. There were variations in the cultivars’ tolerance to the heat stress but, overall, leaf size was stunted, chlorophyll-index estimates increased and tuber size was reduced. As a result, he says, they were able to identify the most heat-tolerant cultivars currently available to Canadian growers.

“We wanted to understand the impacts of high temperatures on potatoes in the northern climate,” Li explains. “It’s possible that potatoes could be grown farther north if the climate warms up, but the issue will be if they will have enough time to reach maturity. Perhaps we will need varieties that mature earlier.”

“It’s possible that potatoes could be grown farther north if the climate warms up, but the issue will be if they will have enough time to reach maturity. Perhaps we will need varieties that mature earlier.”

Li cautions, “Canada grows potatoes one crop per year, and the potato plants need to tolerate hot summer days in order to continue to grow in the fall. These hot days could potentially impact the tuber and quality negatively.”

Tuber size is reduced under heat stress in all varieties tested but, of those that appeared to be the most heat tolerant, many are the offspring of the industry’s long-time standards, such as Shepody. In fact, Li reports that Shepody performed better than most of the varieties in the study. He adds that Atlantic also performed relatively well under the stressful conditions.

“We need to start addressing heat tolerance in potatoes in order to be prepared for the future,” Li advises. “We need to do further research, and we need to be more proactive about saving varieties that are currently important for the potato industry but are heat susceptible.”

“We need to start addressing heat tolerance in potatoes in order to be prepared for the future,” Li advises.

Li’s heat tolerance research is just the tip of the iceberg. He reports wanting to consider improving the performance of plants when they are under stress. Besides developing new varieties, are there cultural practices that could be adopted to reduce the stress from increasing temperatures? For example, how does heat stress affect the growing cycle, and are there production adjustments growers could make to grow potatoes in a warmer climate?

“We are confident that we can largely resolve the issues,” Li comments. “We are working on several levels in this regard and we think we can improve the production of potatoes using both genetic and non-genetic approaches.”

“Understanding the biology, identifying the involved genes, and improving varieties for heat tolerance are priorities for our research team,” Li adds. More research on heat tolerance in potatoes would be useful and could help focus efforts more effectively, he says.

Canada’s moderate climate is good for potato production, but it can be hampered by a short growing season. If it gets too hot, potatoes may not grow in the traditional growing areas, Li cautions. It may be possible to grow potatoes farther north if earlier maturing varieties can be developed, or harvests may need to be completed earlier, resulting in smaller tubers.

Canada’s moderate climate is good for potato production, but it can be hampered by a short growing season. If it gets too hot, potatoes may not grow in the traditional growing areas, Li cautions.

“Climate change is a certainty and temperatures will fluctuate more,” Li says. “Therefore, we need to consider different ideas to reduce heat stress. Perhaps we need to make adjustments at planting or during production. Answering the questions around potato production under heat stress is a priority for my laboratory.”

Li recommends a multi-disciplinary approach going forward. As the climate changes, he suggests all sectors of production need to work together to ensure Canadian potato production remains successful. From a mutational approach to improve heat tolerance of existing varieties, to land and water management, to production activities that can reduce stress during the growing season, Li believes that Canadian potato producers can adapt when the heat is on.

Print this page