Features

Agronomy

Traits and Genetics

Breeders, bees and serendipity

A recent project has corrected misinformation and filled information gaps about the origins of Russet Burbank. It provides crucial genetic information for potato breeders, along with a remarkable tale about how Russet Burbank has come to be a global success.

“Russet Burbank is now the most important potato cultivar in the world. It is the number one processing cultivar in Canada, the United States and the Netherlands, which are the top three frozen French fry-producing countries. It is number one in Europe, North America, and Australia and New Zealand, and it’s right up there in parts of India and China,” says Danielle Donnelly, associate professor in the plant science department of McGill University. “I find it astonishing that a cultivar with origins in the 1890s could still be so important today.”

Donnelly’s research usually focuses on genetic improvement of potato cultivars, but during a sabbatical a couple of years ago at the Potato Research Centre of Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC), she started putting together the story of Russet Burbank. She soon brought in others to help her with the project, including people from the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), McGill, AAFC and McCain Foods Canada Ltd. She notes, “It took a big team to pull all the information together.”

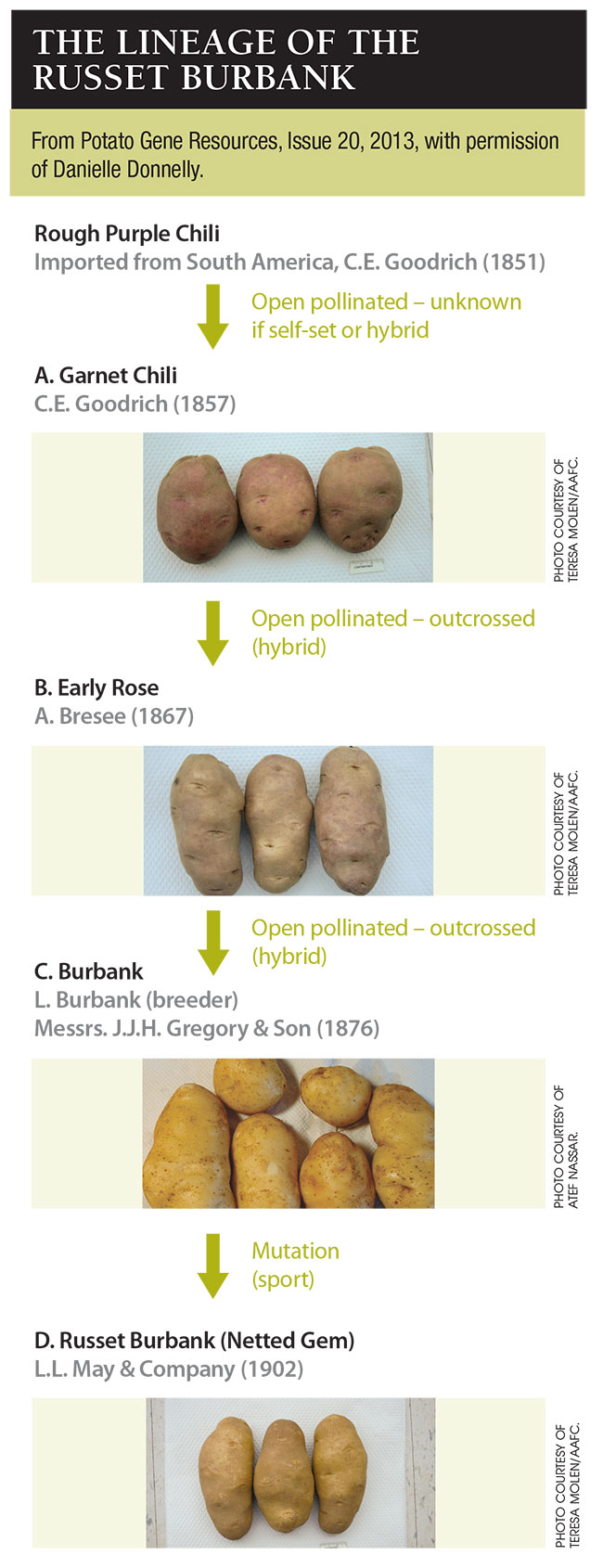

Russet Burbank comes from a line of important cultivars with beginnings in the 1850s. At that time, the potato industry was reeling from the disastrous impacts of late blight, which resulted in the devastating Irish Potato Famine, lasting from 1845 to about 1851. Many of the potato varieties at the time were susceptible to late blight, so breeders and botanists were scouting in South and Central America for potato lines that might have late blight resistance. Rough Purple Chili was one of several South American genotypes brought to the U.S. through the Panamanian Embassy. The amateur botanist C.E. Goodrich tested these lines and selected Rough Purple Chili (released in 1851). The cultivar was thought to have come from Chile (which was spelled “Chili” at the time).

Rough Purple Chili was the parent of Garnet Chili (released in 1857). And from Garnet Chili came Early Rose (released in 1867). These cultivars are very important in North American potato genetics. “In the 1990s, Dr. Stephen Love looked at the genealogy of the top 44 cultivars in the U.S. at the time. He found that Garnet Chili and Early Rose were in the ancestry of all [of] them,” Donnelly says. “It is amazing how small the genetic base is.”

From Early Rose came Burbank (released in 1876), which was named after its breeder, Luther Burbank. As a young man, he made a selection from Early Rose plants in his mother’s garden and came up with Burbank. Then from Burbank came Russet Burbank (released in 1902).

According to Donnelly, the cultivar Burbank was a noticeable improvement over its progenitors. “Garnet Chili is a small, roundish red potato; it is sort of smushed in, almost pointy on one side. Early Rose was considered prettier, with its pinkish colour, and it is longer, bigger and easier to peel than Garnet Chili. Burbank is even bigger and nicer looking than Early Rose, and it could be used for both baking and boiling.”

Luther Burbank sold his Burbank cultivar to a seed company, Messrs. Gregory and Son, but the company let him keep some. Donnelly says, “He went to southern California and started propagating and distributing the cultivar there. A very early USDA, which was just being formed in those days, started promoting the cultivar to all of the potato-growing areas in the U.S. Within just a few years, Burbank was being grown from Mexico all the way up to Alaska.”

Over the following years, various people noted some Burbank tubers had a russet skin. An incorrect but well-known account attributed the discovery of this russeted type to Louis D. Sweet, a Colorado potato grower, in 1914. However, the USDA’s Paul Bethke, who was one of Donnelly’s collaborators on the project, worked with several librarians to look through early U.S. seed catalogues. They determined Russet Burbank was probably originally released in 1902 as May’s Netted Gem by L. L. May & Co. The names Netted Gem and Russet Burbank were often used interchangeably for this cultivar during the next few decades.

Genetic relations

“Over the years, many people have tried to figure out the relationships between Rough Purple Chili, Garnet Chili, Early Rose and Burbank. The breeders of these cultivars each thought the cultivar they had grown in their garden or field had [self-pollinated] and that they were collecting seeds that were ‘selfed’ or inbred,” Donnelly says.

“But all the [genetic] evidence shows these cultivars were actually pollinated from outside. Potatoes are bee pollinated, which tells us those bees really got around, no matter how isolated the breeders thought their fields were. So Garnet Chili, Early Rose and Burbank are hybrids. That was shown in the 1990s through isoenzyme work, and then it was shown again and again through genetic studies and very sophisticated molecular studies.

“These same molecular genetic studies find no difference between Burbank and Russet Burbank, even though the skin is shockingly different. So Russet Burbank is a ‘sport,’ or a mutation, of Burbank,” Donnelly adds.

Thus, as a result of the information brought together in this project, seed companies and germplasm repositories can correct their information on Russet Burbank and its progenitors.

“Breeders need to know how these particular cultivars were produced because the cultivars have been so successful,” Donnelly explains. “If breeders mistakenly thought these cultivars were selfed, they might continue to self them to try to find improvements, when really the breeders should be finding out what the male parent was from the pollen coming in. That is really critical information for a breeder.”

Lucky turns in the path to success

During the early 1900s, Russet Burbank gradually replaced Burbank in popularity. One reason was because people tended to prefer its russeted skin to the thin skin of Burbank. “When Russet Burbank first came along, people were still recalling the Irish famine, and they assumed a potato with a thicker skin would more likely resist late blight. That thicker skin probably does help protect the tuber against a number of bacterial and fungal issues,” Donnelly says.

Another important factor in Russet Burbank’s early success was that Idaho started to promote the cultivar during this same period. She notes, “People in Idaho were trying to find something that would really identify their state and their potatoes. Russet Burbank was a nice-looking potato that grew well for their growers, so they made the cultivar their signature potato, increasing its fame and widespread use.”

As well, the railways publicized the cultivar. “The stories go that some Russet Burbank tubers were so big that they caused problems for the growers because people didn’t want to buy potatoes that were as big as your head. However, someone who was procuring food for the new railways at the time heard about these big potatoes and started serving them on the railway and heavily promoting them as a special treat,” Donnelly says.

A further boost to Russet Burbank’s prominence came in the 1940s, with the growth of fast-food franchises in the U.S. “Who would have known those fast-food franchises would take off like a rocket? Those franchises are fuelled by French fries and burgers. So French fries took off, and frozen French fries became important to distribute to restaurants and to the army during the war,” Donnelly says. “The big, blocky Russet Burbank tubers are perfect for frozen French fries because there is not too much waste, the fries are long, and you can make them in different widths depending on your interest. Plus they have a great taste and fry beautifully, and the tubers store very well.”

The combination of certain traits that make Russet Burbank especially suited to French fry production is another lucky happenstance. Xiu-Qing Li, an AAFC researcher involved in the project, pointed out Burbank and Russet Burbank have “the most extraordinary collection of recessive traits,” Donnelly says. “Such a combination of recessive traits is unlikely to happen very often, and yet all of those characteristics – the tuber’s elongated, blocky shape, large size, very shallow eyes and not very pronounced eyebrows – help make the tuber particularly valuable in the frozen French fry industry.”

A further reason for Russet Burbank’s ongoing success is familiarity. “When people taste French fries in one of the many franchises, they develop a sensory image of what a French fry should be like. Russet Burbank has set a standard for French fry taste and texture,” Donnelly explains. “And then there’s the accumulated expertise in growing, storing, processing, transporting and cooking Russet Burbank French fries, ensuring a very reliable, very delicious product.”

Russet Burbank’s excellent storage qualities are also very important. “I visited Cavendish Farms one summer in July. They had mountains of [Russet Burbank] potatoes to process and they had done their million pounds and more for that day,” Donnelly says. “[Processors] need tubers that store extremely well because they have to be able to process them until the next crop comes in, in the fall.”

These days, the vast majority of frozen French fries in the U.S. and Canada are made with Russet Burbank.

Looking back to the origins of Russet Burbank, Donnelly thinks of Luther Burbank. “His cultivar Burbank was his first discovery, and it turned out to be his most enduring and most important one. However, he is credited with introducing between 800 and 1000 plants to American horticulture, which is hugely impressive. Although he won some awards, he did not receive the respect of his plant breeding peers because he was very unconventional – he wasn’t a scientist, [and] he used intuition and logic and experience to make his decisions,” she says.

“When Luther Burbank produced his cultivar, there was no such thing as plant breeders’ rights and no royalty stream. These days, if he produced such a remarkably popular cultivar, he would be a very wealthy man. And when his cultivar Burbank mutated to become Netted Gem, or Russet Burbank, that would have belonged to him as well because today if you own a cultivar and register it under your name and it mutates, you are owner of that mutation, even if someone else finds it. If Luther Burbank were alive today, the knowledge that his potato cultivar is the most important in the world would make a big difference to his success as a breeder and to the respect he got as a breeder.”

|

|

December 23, 2015 By Carolyn King

The 1902 catalogue from L.L. May & Company in which Russet Burbank (Netted Gem) first appeared. A recent project has corrected misinformation and filled information gaps about the origins of Russet Burbank.

The 1902 catalogue from L.L. May & Company in which Russet Burbank (Netted Gem) first appeared. A recent project has corrected misinformation and filled information gaps about the origins of Russet Burbank.Print this page