Features

Agronomy

Crop Protection

Wireworms on the rise

Potato growers in Prince Edward Island are struggling with escalating wireworm populations. And wireworm problems are on the rise in some other parts of Canada too, impacting potatoes and many other crops. As well, Thimet 15G, the main insecticide for wireworm control in potatoes, is scheduled to be phased out in 2015. So researchers are working on strategies to keep these serious pests at bay, while looking for a “silver bullet” to provide longer-lasting control.

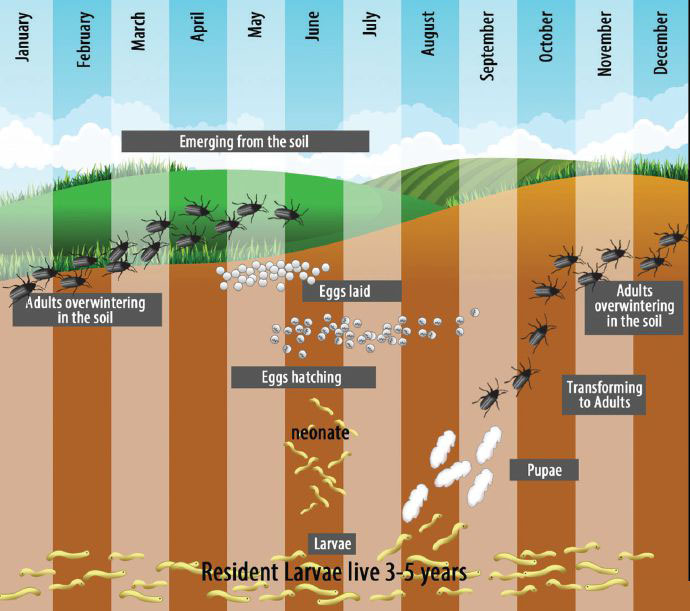

Wireworms are the soil-dwelling larvae of beetles in the Elateridae family, called click beetles. Canada has about 30 wireworm species of economic importance. In most species, the beetles lay eggs in the soil in the spring. A few weeks later, the larvae hatch. The larval stage lasts about four or five years, depending on the species. Then the larvae pupate and emerge from the soil as adults in the spring.

In potato crops, wireworms rise to near the soil surface in the spring to feed on the seed pieces. In the summer, they go deeper to escape hot, dry conditions. As cooler, moister conditions return in late summer, they rise up again and tunnel into the daughter tubers, reducing the marketable yield. The tunnels can also be entry points for potato pathogens. As winter approaches, the larvae descend again to avoid the cold.

Wireworm control is plagued with challenges. For instance, the 30 pest species differ from each other in ways that affect control practices, such as their susceptibility to some insecticides. Because the larvae are hidden in the soil, it is difficult to know how many species, if any, are in a field.

Each generation of wireworms can cause problems in a field for several years. If their preferred crops of cereals and grasses aren’t available, they can feed on other crops. They can go for long periods without food. And they can move to escape unfavourable conditions. As well, because wireworms feed several times during a season, the length of time an insecticide remains effective can be an issue.

|

P.E.I. situation

“Wireworms have been a localized problem in P.E.I. for many years. But in the last few years the populations have increased to the point where the problem is really out of hand,” says Dr. Christine Noronha with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) in Charlottetown.

She started working on wireworms in P.E.I. in 2004 when a grower in Queens County told her he was having a lot of problems with the pest. Since then, she has been using click beetle pheromone traps to get a better understanding of their distribution on the Island. “Initially, we just surveyed in areas where we knew the problem was bad. But we started getting more and more reports of problems in new areas. So we did a major survey across the province in 2009 and a follow-up survey in 2012,” she explains.

The 2009 and 2012 surveys were joint efforts of AAFC and the P.E.I. Department of Agriculture and Forestry. In 2009, they placed 60 traps in fields across all three counties. In 2012, they placed traps in those same fields and additional fields, setting out 85 traps.

“Our results show more fields were infested in 2012 than in 2009. In 2009 some pockets didn’t have any problems; we don’t have any such pockets now. Also the numbers of beetles caught in 2012 were much higher than in 2009, in spite of taking into account the additional traps. Queens County had the highest change in population, with about an eight-fold increase,” says Noronha.

Populations of Agriotes sputator, the most damaging wireworm species in P.E.I., increased in all three counties.

P.E.I. has several wireworm species, and typically at least two species in a field. The pheromone traps are for the three European species found in P.E.I. – Agriotes sputator, Agriotes lineatus and Agriotes obscurus – because those are the only ones for which pheromones are available for purchase.

“One big reason why P.E.I. is having such problems with wireworms is the spread of those European species,” says Dr. Bob Vernon, who leads AAFC’s national wireworm research effort, which is based at Agassiz, B.C.

“Agriotes sputator is known as the potato wireworm because it is a very bad pest of potatoes. The sputator beetle flies quite well so it can invade new areas rapidly, moving about half a kilometre per year. Agriotes lineatus and Agriotes obscurus beetles move primarily by walking, so they invade new areas more slowly. These three species, and especially sputator, have gained a foothold in parts of P.E.I. and are expanding their range and increasing their numbers.”

According to Vernon, another key reason for the increasing problems in P.E.I. is that potato rotations in the province often include cereals and other grassy crops. He says, “Such rotations are good for soil conservation, but they favour the spread of wireworms.”

In P.E.I., the European beetles tend to spread out from non-farmed grassy verges into nearby fields, preferring to lay their eggs in cereals, grasses or pasture. He notes, “If that generation of larvae emerges as adults when a really favourable crop, such as barley or hay, is in the field, they’ll stay and lay all of their eggs there. So the wireworm population in the field will increase by 200 times because that’s about the number of eggs that each female of these European species lays.”

Vernon believes a third reason for the wireworm population boom is the gradual breakdown of long-lasting residues of organochlorine insecticides, which used to be widely used in Canada and around the world. “When applied to the soil, organochlorines did a very good job of killing wireworms, but those insecticides persist in the soil for a long time. For instance, Dr. Fred Wilkinson determined that a single application of heptachlor in the soil would kill wireworm larvae for 13 years,” says Vernon.

Depending on the products and how often they were applied to a field, the residues could be sufficient to kill newly hatched larvae in that field for many years. “So wireworms almost worldwide became a problem of the past because of the organochlorines. But those insecticides have been banned for years, so the soils are losing those residues. And now the fields are wide open for wireworm populations to start to explode,” he says.

|

A look at the rest of Canada

“The organochlorines were a silver bullet – we didn’t have to worry about the wireworm species because they killed every wireworm species. But some of the newer insecticides are more effective on certain species than others, so we need to know which species are in an area to know if a particular insecticide will work,” explains Vernon. “And to make things more complicated, many fields have more than one species; they can have up to five species.”

So Vernon’s research team is working on the daunting task of conducting Canada’s first-ever national wireworm species survey.

Like P.E.I., Nova Scotia has native species as well as the three European species, which are causing problems in many crops. In New Brunswick, wireworms do not appear to be a major problem so far.

“Wireworm problems in Quebec and Ontario are starting to increase. We’ve just finished a three-year study with the Quebec government, so we have a good idea of the species in Quebec; they don’t have the European species yet. We’ll be doing the same type of survey in Ontario in 2014,” says Vernon.

The researchers have identified the primary species on the Prairies. “We’re seeing a huge build-up of some wireworm populations in places like Alberta. Prairie farmers used lindane [Vitavax] as a cereal seed treatment. It killed about 70 per cent of the existing wireworms and about 80 per cent of the baby wireworms in that cereal crop. So they used lindane once every three or four years and that kept the populations under control,” he says.

“Now that lindane is banned, farmers have replaced it with newer insecticides. For example, the neonicotinoids just put wireworms into a coma from which they recover fully. So you can get a good crop stand, but you have new egg laying in that cereal crop and you’re not killing any wireworms in that field. So you have a constant increase in wireworms.”

Cereals are often key crops in Prairie rotations, including potato rotations, so lindane was an important tool.

Prairie potato growers are using Thimet 15G for wireworm control. “In potatoes east of the Rocky Mountains we have basically one insecticide that will reduce wireworm damage by about 90 per cent, and that is Thimet 15G,” says Vernon. Usually Thimet works well, but he says it can be overwhelmed when wireworm populations are enormous.

Vernon’s research team has good information on the B.C. wireworm species, which include native species as well as Agriotes lineatus and Agriotes obscurus. Although B.C. does not have Thimet, Vernon has developed an effective strategy for B.C. potato growers. It combines a neonicotinoid seed treatment (clothianidin, Titan) and an in-furrow spray with chlorpyrifos (Pyrinex). However, clothianidin is not quite as effective on some wireworm species in other parts of Canada, and chlorpyrifos cannot be used on potatoes that will be sold into the U.S. because no minimum residue levels have been established for the U.S.

Searching for a new silver bullet

For many years, Vernon and his colleagues at AAFC have tested virtually every insecticide that has come along for its effects on wireworms in various crops. This research shows neonicotinoid and pyrethroid products can protect the crop they are applied on, but he wants to find something like lindane that also protects the following crops in the rotation.

“We are always looking for a new silver bullet, for something that will effectively kill wireworms, not just knock them out, like the neonicotinoids, or repel them, like the pyrethroids.”

The irony is that Vernon has already found a silver bullet.

“Our big hope was fipronil. It is registered in the United States on potatoes for wireworm control and it was registered on corn. We found that fipronil kills all species of wireworms very effectively. And we came up with a strategy to put it on cereal crop seed. This strategy combined very low amounts of fipronil – less than one gram of fipronil per hectare – with low amounts of a neonicotinoid. The neonicotinoid gave us an exceptional crop stand and the fipronil eradicated the existing wireworm populations, including the baby wireworms produced that year. So with one application of this blend, we could inexpensively control wireworms for three to four years, just like lindane. And it was even more effective than lindane with 60 times less insecticide,” explains Vernon.

“Whether or not that strategy ever sees the light of day is up to the chemical industry to either bring fipronil into Canada or not. That has not happened yet, and it may not happen.”

AAFC has been working with Health Canada’s Pest Management Regulatory Agency (PMRA) to find options for controlling wireworms, including alternatives to Thimet 15G (phorate), which is to be phased out due to environmental concerns.

“In 2006, under a joint Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada/Health Canada Pesticide Risk Reduction Program, the pesticide risk reduction strategy for wireworm was developed and centered on the need to find lower risk replacement pesticide products and practices for the control of wireworm in Canadian agriculture,” says Margherita Conti, director general of PMRA’s value assessment and re-evaluation directorate.

“In 2008 . . . the PMRA initiated a transition trategy for phorate to address this loss of an older chemistry and to promote the transition toward reduced risk pest control options. There are continuing consultations with researchers, growers and grower associations, processors, provincial specialists and pesticide companies towards the goal of finding replacement products. To date, chlorpyrifos has been registered for wireworm control in B.C., and clothianidin has been registered for suppression of wireworm in potatoes.”

Thimet was previously scheduled to be phased out by 2012, but that deadline was extended. Currently, the last date of use of Thimet 15G by growers and users is set for August 1, 2015. “Any extension would have to consider the outcome and timeline of the ongoing review of a potential replacement,” Conti notes. “There has been an application received by the PMRA to register bifenthrin [Capture] for control of wireworm on potatoes. There has not been a decision made at this time [April 2014] to extend the registration of Thimet.”

She adds, “The PMRA is aware of the critical nature of the wireworm situation in Canada. Consultations are continuing with researchers in AAFC, provincial officials and other stakeholders regarding the wireworm situation.”

Next steps

Over the next four years, with funding through Growing Forward 2, Vernon, Noronha and their colleagues are expanding their work on wireworms, including options for hot spots with huge populations.

Noronha has developed a rotational strategy for P.E.I. potato growers. Her research shows that growing either brown mustard or buckwheat for two years before growing potatoes can reduce tuber damage by about 80 per cent or more.

When brown mustard plants are disked into the soil, a natural chemical in the plant breaks down to form isothiocyanate, which acts like a fumigant to kill wireworms. As well, brown mustard roots have natural chemicals that are toxic to wireworms. The mechanism causing buckwheat’s effect on wireworms is unknown at present. Both crops control all of the wireworm species found in P.E.I.’s agricultural areas.

Noronha and her provincial colleagues are talking with P.E.I. growers about this strategy and how to implement it. For growers in severely affected areas, the approach is to grow two crops per season of either brown mustard or buckwheat, and to do that for two years in a row. “Because brown mustard and buckwheat are both short-season crops, the farmers have to grow two crops a year. They plant the crop in June. At the end of July, before the crop has gone to seed, they disk it into the soil, and then they plant the second crop. Any wireworms that didn’t die with the first crop are targeted with the second crop. The growers leave the crop standing over the winter for soil conservation cover,” explains Noronha. The growers repeat those steps for another year, then in the third year they plant potatoes.

For the strategy to work effectively, the control crops can’t set seed. So the farmers have the costs of growing the control crops but they are not earning any money from them.

She suggests potato growers with severe infestations use Thimet along with the rotational strategy: “Hopefully that will bring some of the populations down to manageable levels.” The rotation also provides an option for growers if Thimet is no longer available.

For P.E.I. growers who are just beginning to have wireworm problems, she recommends planting brown mustard in August, before planting potatoes in the following year. Growers who don’t have a wireworm problem so far can use the same approach, but they only need to plant a control crop once in while.

Noronha and her P.E.I. colleagues are working on various other wireworm projects, including another provincial survey to be conducted in 2016.

Vernon is continuing his insecticide efficacy studies to find a lindane-like substitute that can be used on cereal crops to provide wireworm control for several years.

He’s also adding a new focus to his research: killing the beetles before they can lay their eggs. This approach would not control the larvae already living in a field. It is aimed at areas where wireworm populations are exploding.

Vernon and his colleagues are working on a variety of methods to kill the beetles. For instance, he is using pheromone traps to time field spraying of an insecticide, such as a pyrethroid or a botanical spray like pyrethrin. One of Vernon’s colleagues, Todd Kabaluk, is evaluating methods to apply Metarhizium anisopliae to kill the beetles. This fungus is highly lethal to click beetles and does not harm the key beneficial insect species they have tested. The researchers are also investigating environmentally safe ways to control the beetle populations in grassy verges, such as using botanical sprays or mass trapping and mating disruption.

“This insect has been a nightmare,” says Vernon. “Farmers are losing crops, and the problem is going to get worse. If we had access to products that other countries have access to already, we would not have a wireworm problem today. It’s very discouraging to have to look at spraying fields to pre-emptively control beetles just in the hope that you can slow them down.”

February 10, 2015 By Carolyn King

Print this page