Features

Agronomy

Diseases

Researchers look to soil for scab solutions

For potato growers around the world, common scab is a constant vexation. Causing millions of dollars in losses each year, common scab is difficult to control. Recent research, however, has identified options for suppressing the disease, if not getting rid of it all together. Some of the research centres on what soil properties make scab more conducive, while other studies look at natural products that can slow the spread.

“Scab is a troublesome disease,” admits Robert Coffin, a potato agrologist in Prince Edward Island. “There are different genetic strains of scab as well; there are at least five species, so it’s a constant problem. For example, common scab and powdery scab are two different organisms, but both diseases can cause losses in sales because scab infested tubers cannot be sold for table, processing or seed.”

While large strides have been made to control scab, such as using natural bacterial products, seed treatments, soil fumigants, and attempts to find genetic resistance, the disease continues to confound researchers and growers alike. Management options are limited but several help, such as planting varieties with “reasonable resistance” or fumigating the soil, which has proven successful, although is it not permitted for use everywhere.

Some diseases can’t survive in the soil without a host, according to Claudia Goyer, a research scientist with the Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) Fredericton Research and Development Centre. But Goyer says scab can live successfully in the soil without potatoes being present, making it a problem when potatoes are planted.

“The scab bacteria grows on organic matter, like plant residues,” Goyer explains. “What makes it difficult is there are areas of fields that are infested while others are healthy and we do not know why. We now believe there is something different between scab-infested or healthy areas, like soil properties or microbial communities, that could be conducive or suppressive to scab.”

To test this theory, Goyer and her colleagues examined either healthy or scab-infested areas of nine potato fields in Prince Edward Island, New Brunswick and Quebec. The same variety of potato – Red Pontiac – was grown in each field and the team gathered soil samples three times during the year. Several soil properties (including pH, organic carbon, micronutrients and soil texture) were measured to attempt to determine the difference between the soils that contained scab and those that didn’t.

“We are trying to learn if it is something physical, chemical or biological, such as soil microbial communities in the soil, that promotes scab,” Goyer explains. “Some microbial communities suppress scab.” Not surprisingly, she also discovered that the greater the presence of the scab bacteria, the greater the disease pressure. “We are still analyzing our data, but we are seeing a correlation between scab and pH levels, with more scab in neutral pH soil. We are also seeing that soil carbon to nitrogen ratio, and nutrients including potassium, magnesium and calcium, were correlated with scab severity, but we aren’t sure why yet.”

Advancements in soil science are making it possible for the researchers to analyze soils more effectively and they are also able to assess new control options more efficiently. Coffin conducted research on Microflora Pro, a natural product that contains two species of Bacillus bacteria. He says the product worked really well in 2015, but the results were inconsistent in 2016.

“Bacterial cultures don’t always stay stable in storage or in soils,” Coffin explains. Therefore, understanding scab and how it infects soil, and continuing work to breed resistant potato varieties, would offer better disease management options.

Goyer’s work on analyzing soil and understanding why certain fields are infested with scab may also help the developers of microbial products create formulations that will work best. The advent of more sophisticated soil science research is paving the way for a better understanding of what bacteria will work best in soil.

“We can truly study soil communities so much more than we could years ago using next-generation sequencing,” Goyer says. “We can see how diverse the soil bacteria and fungal communities that are present in soil are now because of the depth of sequencing. We can capture most of the species present with this approach.” This type of work will help explain the difference in the diversity of soil microbial communities between healthy and scab-infested areas in potato fields.

“Once we understand better what a healthy soil microbial community is,” Goyer continues, “we can see if we can change soil microbial communities so they suppress scab using agricultural practices, inputs like manure and compost, or use of natural bacterial products that suppress scab.

“In the future, we will be able to harness the power of the soil,” Goyer says. “We may be able to manipulate bacteria communities to improve all crops and we could use them to suppress disease.”

Both Goyer and Coffin approve of the idea of using one bacteria to control another. In theory, the best solution would be to combine several bacteria into one product to help with stability, reduce the potential of resistance developing and, possibly, offer balance in the soil. But with so many variables, it takes a great deal of research to get it right.

Goyer says one possibility is that a certain bacteria could be targeted to where it is needed most, similar to the way precision fertilizer application works. Higher amounts of scab-fighting bacteria could be targeted to where soil tests show a high concentration of the disease, and less could be added where scab pressure is low, creating an overall balance across the field.

“Progress is being made,” Coffin says. “With 30,000 to 40,000 genes in a potato plant, it’s like a giant Rubik’s cube when trying to breed a potato with all the desired traits.”

Of course, scab resistance is only one of the desirable traits, which makes finding a solution in the soil another option for controlling scab – and one that Goyer believes shows great promise going forward.

March 28, 2017 By Rosalie I. Tennison

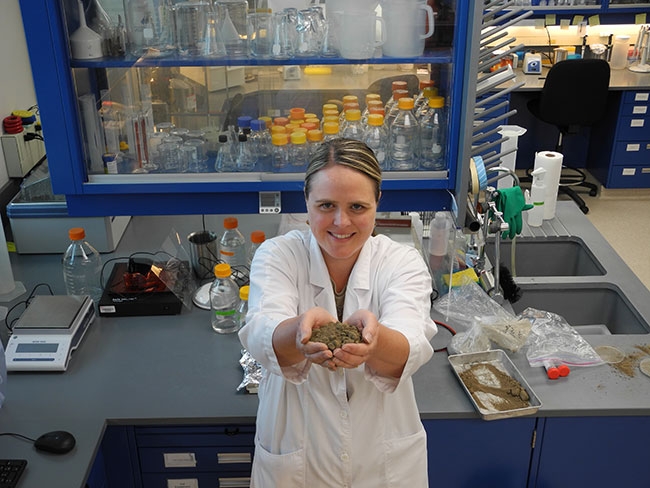

Claudia Goyer is researching the link between soil microbial communities and common scab. For potato growers around the world

Claudia Goyer is researching the link between soil microbial communities and common scab. For potato growers around the worldPrint this page